This article is the first part of a series on the history of private credit investing. For access to the rest of the series, read part two and part three.

Note: For the purposes of this article, “private debt” (and “private debt markets”) reference the overall private/non-bank lending industry, whereas “private credit” (and “private credit investing”) references investments made in this industry.

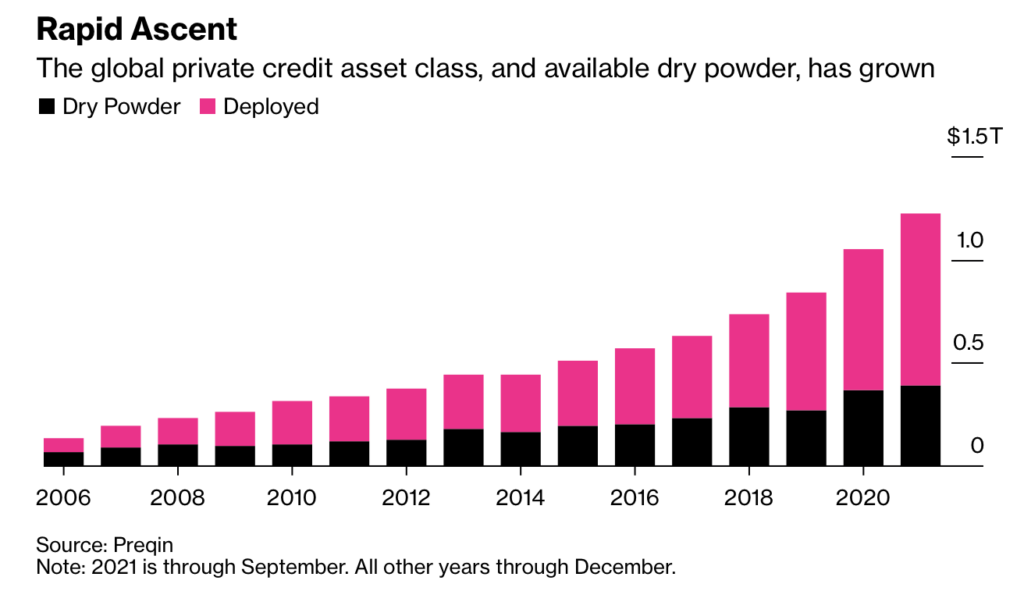

The total leveraged finance market, defined to include high-yield leveraged loans and high-yield bonds, reached $3 trillion in mid-2021, according to S&P Global1. The size of this market has doubled since the end of the Great Financial Crisis in 2010. Though this growth seems impressive, it is only half of the growth experienced by the private debt markets, which have quadrupled in size over the same period, reaching an estimated $1.2 trillion in September 20212 (according to data provided by Preqin).

The private debt market has grown steadily for many years although the growth has been especially dramatic since the end of the Great Financial Crisis. Over the years, it evolved into a much deeper, complex and varied market, encompassing companies of all sizes and creditworthiness and an equally diverse range of investors, including retail market participants through investment platforms such as Percent.

To understand how this trillion-dollar industry came to be, one must chart its history from its foundation, to its evolution, all the way to present day events. Seeing as this market is private, it is difficult to obtain precise data, although most reliable sources generally agree on headline figures.

Understanding U.S. Private Placements

For many decades, the private debt market in the U.S. meant one thing: U.S. private placements.

Private placements are the placement of debt or equity securities by a company (issuer) to an investor or group of institutional investors in a private transaction, as contrasted to the better-known and highly regulated public market.U.S. private placements refer to middle-market or occasionally larger companies raising long-term debt from one or more U.S. life insurance companies including Prudential, MetLife, New York Life, TIAA-CREF, Northwestern Mutual, and others.

In most instances, the debt – referred to as “notes” – is unrated by the large rating agencies, but it is rated privately by the National Association of Insurance Commisioners (“NAIC”). NAIC ratings tend to be much more lenient to middle-market companies than the public rating agencies like Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, which often penalize companies simply because of their size. U.S. private placements normally have maturities of seven to 15 years — beyond the length of time that banks are willing to lend — and they almost always have fixed-rate coupons. Each transaction is bespoke, meaning that the pricing and terms of each U.S. private placement are negotiated privately between the issuer and the participating group of life insurance company investors.

Some companies issuing U.S. private placements are publicly listed, but more often than not, they are either private U.S. companies or foreign listed companies that do not wish to comply with the stringent SEC-reporting requirements necessary to issue a public bond in the U.S. market. From the perspective of U.S. life insurance companies, private placements are a way to invest in high quality, long-duration assets to match their long-duration liabilities. These investments are almost always on a “buy-and-hold to maturity” basis. The traditional U.S. private placements market is tailor-made for structured or secured transactions, too, like infrastructure/project financings and asset-based securities, with the latter often involving esoteric asset classes. Annual new issue volumes in the U.S. private placements market are normally between $80 billion to $100 billion each year3.

The 1980s: Private Placements Broaden

The U.S. high-yield market came into existence in the late 1970s/early 1980s. This public market alternative provided small- and middle-sized companies that were not investment-grade rated with the ability to access long-term, fixed-rate debt financing, often unsecured and/or subordinated. Until that time, both the public corporate bond market and the U.S. private placements market were focused on investment-grade rated companies only, so the new high-yield bond market opened a long-term debt financing avenue for lesser-rated companies.

Since the high-yield market was public, the disclosure and process for issuing high-yield bonds was similar to that for selling shares (i.e. equity), governed by the SEC. The development of this market opened an important financing alternative for middle-market companies, which could now raise fixed-rate debt in the bond market that would often slot between senior secured bank financing and equity in a company’s capital structure. The high-yield market became an important financing vehicle for small- and middle-market growth companies that found banks too conservative and often unwilling to lend (or lend in the necessary amount), and equity investors too expensive.

The new high-yield market also pushed private equity firms into the forefront since high-yield bonds could be used to increase total leverage in leveraged buyout transactions, enabling private equity firms to pursue larger acquisition targets and to increase the overall purchase price. There were drawbacks to the high-yield market, including substantial access costs, the requirement to have two public credit ratings, extensive and SEC-compliant disclosure, and a “soft” minimum new issue size of $125 million. (This was done to ensure there was sufficient secondary market liquidity since the bonds would be publicly traded after they were issued).

As exciting and high-profile as the high-yield market would become, it was unfortunately unable to meet the needs of smaller companies that needed less than $125 million of financing, companies which were private and wanted to remain so, or companies that wished to avoid getting public credit ratings. To address the financing needs of smaller companies, a private market alternative to public high-yield bonds began to develop, known as the “mezzanine market.” The early investors in private mezzanine securities were select insurance companies and S&Ls (pre-S&L crisis of the late 1980s/early 1990s), but the most important investor contingent that developed during the 1990s were dedicated mezzanine funds focused specifically on investing in private mezzanine financings.

Mezzanine debt was generally structured to achieve a target return of 18% to 20%, obtained through a combination of a (contractual) coupon payment and equity warrants. Sizes could be $10 million to $75 million or more, but substantially below what the public high yield market required. More often than not, one mezzanine fund would provide the entire financing for a company. Mezzanine financing – similar to (public) high yield bonds – was especially attractive to growth companies and to companies that had exhausted their senior debt capacity.

To read the next part in this series on the History of Private Credit, click here.

1Source: S&P Global, “After risk-on run, U.S. leveraged finance market tops $3 trillion in size”.

2Source: Preqin. The components in the bar graph labeled “dry powder” refers to the proceeds at debt funds that have not yet been invested or deployed.

3Source: The Private Placement Monitor, here.