A whole business securitization (WBS) is a transaction in which an issuance of notes is secured by a pool of income-generating assets (other than “financial assets” like loans or receivables) that make up substantially all the revenues of a business.

Collateral and Industries

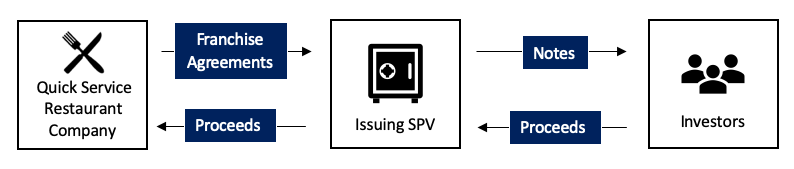

The underlying cash flows in a WBS are most often royalties of one sort or another generated by contracts like restaurant franchising and music licensing agreements. As an example, quick-service restaurant chains (like Taco Bell and Wendy’s) are frequent sponsors of WBS transactions. These businesses hold large amounts of assets, namely franchisee agreements, that generate a steady stream of income, and the business may wish to use those assets to unlock a source of financing.

This can be achieved by selling these assets to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), separate from the sponsoring company. The proceeds from the sale might then be used to fund an acquisition, refinance debt, or fund capital improvements. The SPV, in turn, finances the purchase of the royalty streams by issuing notes to investors; the income generated from the royalties is used to pay interest and principal payments on the notes.

In the case of a quick-service restaurant WBS, royalties from franchise agreements can often be complemented by other revenue streams in a transaction. These include royalties from trademarks, leases on real estate holdings, income from company-owned stores, and other miscellaneous fees.

Sample Structure for a WBS

Credit Support

Investors in a WBS look to the income-generating assets to provide for the repayment of their notes. However, like other securitizations, there are credit enhancements that provide some protection to noteholders. First, the cash flows in the securitization usually greatly exceed the minimum required to make the required payments on the issued notes. Because of this cushion, even if revenues fell for some economic or operational reason, noteholders would not necessarily suffer a default.

It is most typical for debt service coverage ratios (the ratio of available proceeds to required interest and principal payments) on WBS transactions to exceed 1.6x. A ratio of 1.6x means that proceeds can come in almost 40% less than expected until losses are likely experienced on the notes.

And that’s not usually the only credit enhancement, as many transactions also feature a cash reserve account. This cash reserve is usually sufficient to make a quarterly interest payment. This provides some secondary support if proceeds on the underlying assets come in lighter than anticipated.

For Investors

Investors in a WBS should note that the health and skill of the sponsor matter to a higher degree than is typical among securitizations. This is because the cash flows generated by the underlying assets are usually tied to the revenues of a business.

In the example of quick-service restaurants, the royalties due are usually a percentage of franchised restaurants’ revenues. As such, successful marketing, enforcement of franchise agreement terms, defense of trademarks, and other functions are critical to ensuring proceeds do not erode with time.

Another important feature of a WBS is that the pace of amortization is usually dependent on the amount of proceeds available to repay noteholders. Notes can have both required and excess amortization components with the latter being variable, depending on the amount of income generated from the underlying assets. Thus, while the notes often have a legal final maturity 10 years or longer from the issuance date, a transaction’s anticipated repayment date is usually much sooner.

Please note this post is meant to give a brief and high-level overview of a WBS. Investors should review offering documents to get an understanding of the full risks involved in any transaction.